Native Quinault artisans share the tradition, language, spirituality of a nation

Story by Juliana Wallace

On the shore of the Quinault River in Taholah stands a 20-foot-tall figure of a thunderbird, a man, and a woman holding a king salmon. Both imposing and beautiful, the figure serves as a memorial to Quinault fisherman and pays homage to the journeys of both the Quinault people and the fish that play a prominent role in their culture and livelihood.

Artist Guy Capoeman (“Naçaktuah” in the Quinault language), his son Cecil, and his brother Jeff carved most of the figure out of a single piece of old growth cedar. A thousand years old, the tree watched the passing of generations of Capoeman’s ancestors who lived along the Quinault River.

“What uniquely makes us Quinault is our connection to this land that goes back so many generations. Imagine what this tree saw or heard in its lifetime and what it experienced,” mused Capoeman, 55, who has served as the president of the Quinault Nation since 2022.

The Quinault people did not historically have totem poles. Instead, pieces like this would typically be crafted as “house posts,” meant to stand inside a traditional long house, supporting the main beams and often representing the owner’s spirit helper.

Combining function with form, the house posts illustrated stories and themes important to Quinault culture. And they historically played a prominent role in the songs and dances performed for medicinal purposes or spirit representation.

“As a tribal leader, you’re responsible for cultural preservation, for community enrichment. In order to champion the (Quinault nation’s) sovereignty, the people have to know who they are,” explained Capoeman.

To that end, he and his sons and brother have designed and carved several of these house posts for locations around the Pacific Northwest.

“With these pieces, I try to leave a mark that shows our people, what we are and what we have been, what we can be and how we can grow in today’s age. We wanted to put a pinpoint in history for people to wonder and ask what it means,” he said.

The fishermen’s memorial in Taholah used just one half of an ancient cedar tree. Out of the other half, Capoeman and his crew built a dugout ocean canoe for a tribe in Southern Oregon. While he has now designed and built more than 30 canoes, his first canoe required a significant learning curve.

In the late 1980s, Capoeman attended the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland to learn the techniques of painting and carving that would allow him to use art to share the Quinault story with the tribe and with the world. When he came home to Taholah on break, the tribal elders approached him and asked him to carve an ocean canoe for the Washington State centennial celebration.

“They showed me this old growth log that was nine feet wide at the butt and 39-feet long,” he remembered. “It was humongous!”

The Quinault people had mastered the design of ocean canoes over many generations, but no one had practiced the art in nearly a hundred years. However, several men in the tribe made river canoes, and they helped Capoeman and his crew of artisans with the general principles of canoe building. Careful research and practice filled in the gaps.

“We named that first canoe May-ee, which means ‘the beginning.’ She has a lot of miles on her, and she’s been in a lot of rough waters, but she’s beautiful,” said Capoeman proudly.

While the 34-foot-long May-ee and his other early canoes were built as classic dugouts from a single log, Capoeman has since evolved his design and methods. Building those canoes and crewing them over hundreds of miles of ocean waters helped him understand the form and refine his process.

Now he builds canoes out of boat-stock fir strips stretched around forms that he designed. After sanding and smoothing the fir, the artisans cover it in fiberglass cloth and then epoxy resin. The precisely crafted angles give the canoes exceptional efficiency.

“When it’s done, it looks just like a dugout and performs just as well, if not better,” explained Capoeman. “These canoes are faster, lighter, more stable. In fact, I believe the old canoes were actually more like this than the heavier dugouts you see today.”

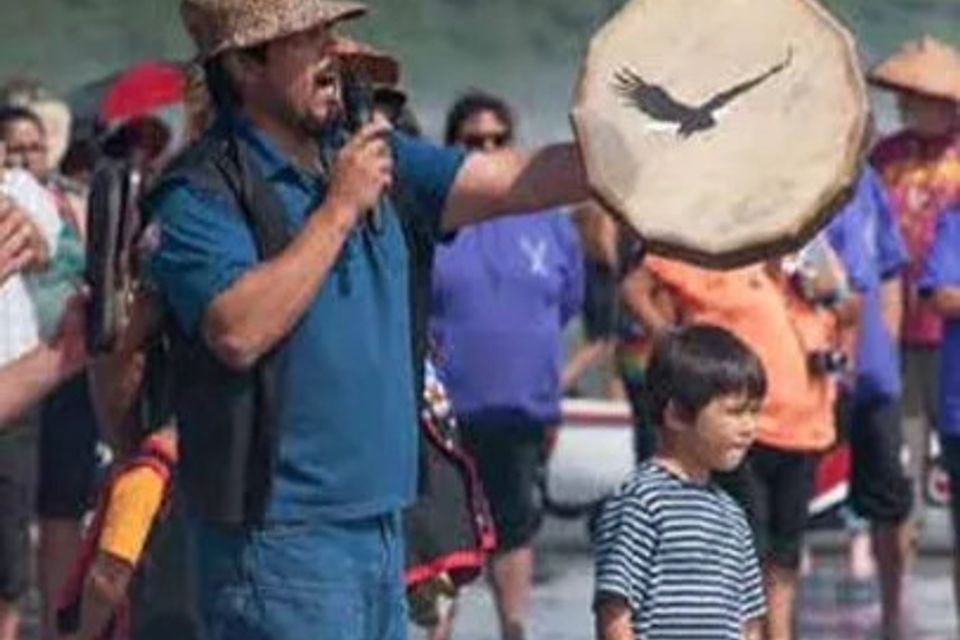

The canoes, like the house posts or traditional songs, help to share an important part of history and cultural identity in a way books cannot. Quinault youth see the stories represented in the carvings, paintings and traditional dances. They learn the language through songs and stories.

“Identity is so important for your foundation as a people. You have to know where you came from, who your community is. These things will change their lives,” emphasized Capoeman.

The fishermen’s memorial in Taholah used just one half of an ancient cedar tree. Out of the other half, Capoeman and his crew built a dugout ocean canoe for a tribe in Southern Oregon. While he has now designed and built more than 30 canoes, his first canoe required a significant learning curve.

In the late 1980s, Capoeman attended the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland to learn the techniques of painting and carving that would allow him to use art to share the Quinault story with the tribe and with the world. When he came home to Taholah on break, the tribal elders approached him and asked him to carve an ocean canoe for the Washington State centennial celebration.

“They showed me this old growth log that was nine feet wide at the butt and 39-feet long,” he remembered. “It was humongous!”

The Quinault people had mastered the design of ocean canoes over many generations, but no one had practiced the art in nearly a hundred years. However, several men in the tribe made river canoes, and they helped Capoeman and his crew of artisans with the general principles of canoe building. Careful research and practice filled in the gaps.

“We named that first canoe May-ee, which means ‘the beginning.’ She has a lot of miles on her, and she’s been in a lot of rough waters, but she’s beautiful,” said Capoeman proudly.

While the 34-foot-long May-ee and his other early canoes were built as classic dugouts from a single log, Capoeman has since evolved his design and methods. Building those canoes and crewing them over hundreds of miles of ocean waters helped him understand the form and refine his process.

Now he builds canoes out of boat-stock fir strips stretched around forms that he designed. After sanding and smoothing the fir, the artisans cover it in fiberglass cloth and then epoxy resin. The precisely crafted angles give the canoes exceptional efficiency.

“When it’s done, it looks just like a dugout and performs just as well, if not better,” explained Capoeman. “These canoes are faster, lighter, more stable. In fact, I believe the old canoes were actually more like this than the heavier dugouts you see today.”

The canoes, like the house posts or traditional songs, help to share an important part of history and cultural identity in a way books cannot. Quinault youth see the stories represented in the carvings, paintings and traditional dances. They learn the language through songs and stories.

“Identity is so important for your foundation as a people. You have to know where you came from, who your community is. These things will change their lives,” emphasized Capoeman.

That Quinault identity figures prominently in the canoes he carves, the songs he shares in the Quinault language, and the paintings through which he represents traditional Quinault legends. And just as he learned from his elders stretching back through many generations, Capoeman continues to pass the traditions and skills down to his own children and the youth of the tribe.

Those wishing to see Capoeman’s art in person have several options. They can view the house post on Quinault Street in Taholah or another near the boatyard in Gig Harbor. The Quinault Resort in Ocean Shores displays his portrait of Chief Taholah II. And travelers driving east through Aberdeen will see Guy and Cecil Capoeman’s “Kape Jiluupak” mural on the west side of the Morck building.

Whether in a mural, on a canvas or house post, or in the form of an elegantly built canoe, Capoeman offers a glimpse into the history and identity of the people who have watched this land from time immemorial.

Anyone who would like to commission a piece or find out more about Capoeman’s art can contact him via e-mail at gcap1991@gmail.com.

Those wishing to see Capoeman’s art in person have several options. They can view the house post on Quinault Street in Taholah or another near the boatyard in Gig Harbor. The Quinault Resort in Ocean Shores displays his portrait of Chief Taholah II. And travelers driving east through Aberdeen will see Guy and Cecil Capoeman’s “Kape Jiluupak” mural on the west side of the Morck building.

Whether in a mural, on a canvas or house post, or in the form of an elegantly built canoe, Capoeman offers a glimpse into the history and identity of the people who have watched this land from time immemorial.

Anyone who would like to commission a piece or find out more about Capoeman’s art can contact him via e-mail at gcap1991@gmail.com.